What is golf medicine?

Golf Medicine

Golf medicine is a sub-discipline of sports medicine focused on injury prevention, treatment, safe and efficient return to golf after golf-related injuries as well as performance optimization and health benefits as they relate to golf.

Generally speaking, regular exercise has been well studied to have positive benefits in reducing coronary heart disease (Berlin 1990, Ekelund 1988, Leon 1987), hypertension (Hagberg 1990), non-insulin-dependent diabetes (Helmrich 1991), colon cancer (Lee 1991), bone health, fall risk and overall mortality (Paffenbarger 1993, Blair 1995, Hakim 1998). A randomized control trial by Parkkari et al in 2000 demonstrated regular golf course walking has been shown to reduce weight, waist circumference, abdominal skin fold thickness, and significantly increase “good cholesterol” or high-density lipoprotein (HDL) in golfers. With all these benefits do come preventable sport-specific risks.

The majority of golf-related injuries are overuse injuries (83%) due to repetitive motion where poor swing biomechanics, hitting the ground and excessive play or practice play a role (Goshenger et al 2003). Injury prevention begins with identifying specific deficits and poor mechanics that may portend injury. The Titleist Performance Institute (TPI) Screen is a standardized screening method for golfers that pairs corrective exercises with identified deficits to minimize injury risk. In recent years, golf-specific prevention programs have been developed such as The Golfer’s Fore (Thomas et al 2023) and Golf-Related Injury Prevention Program (GRIPP, Gladdines et al 2022) which vary in the context they are performed and age groups they are intended for, but rigorous randomized controlled trials have yet to be published to assess their efficacy. Prevention programs should be individualized as injury patterns vary among golfers.

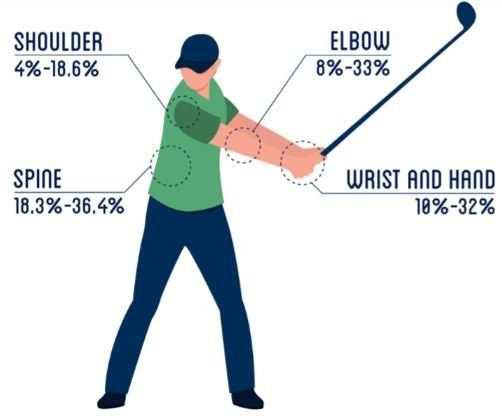

Gosheger et al compared injury patterns between professional and amateur golfers and found that while professional and amateur golfers both suffered from shoulder and back injuries, amateur golfers were more likely to report elbow injuries while professional golfers were more likely to have wrist injuries. In recreational golfers, Gosheger reported the distribution of back and upper limb injuries to be 4.0-18.6% in the shoulders, 18.6-36.4% in the back, 8.0-33% in the elbow, and 10-32% in the wrist. A systematic review by Baker et al in 2017 demonstrated knee-related injuries ranging from 3-18% of all injuries and while there was no predilection by skill level or sex, it did find older players were at risk. This isn’t a surprise as prior literature demonstrates lead knee experiencing compressive loads ranging form 100-440% of bodyweight during the golf swing (Baker 2017), but there is data to demonstrate the protective benefits of a warm-up routine.

Warm-up routines were found to have a positive effect on decreasing injuries if they were at least 10 minutes long (Gosheger 2003). A systemic review by Ehlert et al 2019 found that in seven observational studies, many golfers were found to not perform warm-ups or perform warm-ups that were short in duration. A study by Fradkin et al in 2005 found that recreational golfers are 3.2 times more likely to report an injury when they do not perform a warm-up. Studies suggest the effect of a proper warm-up goes beyond just injury prevention. One study of youth golfers by Coughlan et al in 2018 demonstrated a combined dynamic physical and club warm-up improved club head speed (CHS) and self-reported shot quality in youth golfers, however, a club warm-up alone didn’t seem to elicit the same improvements. CHS and other performance parameters can be optimized through strength and conditioning and flexibility programs.

A study on the importance of transverse plane flexibility by McHugh et al 2022 demonstrated that proficient golfers had significantly better flexibility than average golfers as well as greater pelvis-trunk separation during the swing, known as the “x-factor” in golf. In 2004, Tsai et al demonstrated a negative correlation between hip abduction strength and handicap (meaning stronger hip abductors was associated with lower handicap) underscoring the importance of lower body strength in the golf swing. Another study by Wells et al in 2009, showed that grip strength showed the highest correlation to score, both in dominant and non-dominant arms. A small prospective study out of Utah Valley University also showed grip strength to be highly correlated to swing speed, corroborating Wells’ findings.

A systematic review on the effects of resistance training on club head speed (CHS) and hitting distance (HD) by Uthoff et al in 2021 found multiple important findings:

- Resistance training positively affects CHS and HD regardless of sex or skill level when a combination of non-specific and golf-specific training is utilized

- Greater improvements of CHS and HD were seen with incorporation of high golf-specific ballistic methods

- Neuromuscular training adaptation may improve hitting performance in as little as 8 weeks

- Generally, 3-4 sets of 5-15 rep programs demonstrated the largest effect on increasing CHS and HD

- Effective schemes included:

- Neuronal scheme (85-100% of 1 rep max) with 1-6 reps/set

- Hypertrophic scheme (60-80% of 1 rep max) with 8-12reps/set

- Low-load ballistic training with medicine balls, pulleys or elastic tubing

Dr. Thomas is Titleist Performance Institute (TPI) Certified and at TSARO, we specialize in the treatment of golf injuries and work as a multiple-disciplinary network of athletic trainers, physical therapists, strength and conditioning specialists, and allied health professionals to not only prevent and treat injury, but boost performance. If you have an injury or you are looking to stay injury-free and improve your performance, contact us today.

References

Berlin JA, Colditz GA. A meta-analysis of physical activity in the prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1990 Oct;132(4):612-28. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115704. PMID: 2144946.

Ekelund LG, Haskell WL, Johnson JL, Whaley FS, Criqui MH, Sheps DS. Physical fitness as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in asymptomatic North American men. The Lipid Research Clinics Mortality Follow-up Study. N Engl J Med. 1988 Nov 24;319(21):1379-84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811243192104. PMID: 3185648.

Leon AS, Connett J, Jacobs DR Jr, Rauramaa R. Leisure-time physical activity levels and risk of coronary heart disease and death. The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. JAMA. 1987 Nov 6;258(17):2388-95. PMID: 3669210.

Helmrich SP, Ragland DR, Leung RW, Paffenbarger RS Jr. Physical activity and reduced occurrence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1991 Jul 18;325(3):147-52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107183250302. PMID: 2052059.

Lee IM, Paffenbarger RS Jr, Hsieh C. Physical activity and risk of developing colorectal cancer among college alumni. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991 Sep 18;83(18):1324-9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.18.1324. PMID: 1886158.

Paffenbarger RS Jr, Hyde RT, Wing AL, Lee IM, Jung DL, Kampert JB. The association of changes in physical-activity level and other lifestyle characteristics with mortality among men. N Engl J Med. 1993 Feb 25;328(8):538-45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302253280804. PMID: 8426621.

Blair SN, Kohl HW 3rd, Barlow CE, Paffenbarger RS Jr, Gibbons LW, Macera CA. Changes in physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy and unhealthy men. JAMA. 1995 Apr 12;273(14):1093-8. PMID: 7707596.

Hakim AA, Petrovitch H, Burchfiel CM, Ross GW, Rodriguez BL, White LR, Yano K, Curb JD, Abbott RD. Effects of walking on mortality among nonsmoking retired men. N Engl J Med. 1998 Jan 8;338(2):94-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801083380204. PMID: 9420340.

Lee IM, Hsieh CC, Paffenbarger RS Jr. Exercise intensity and longevity in men. The Harvard Alumni Health Study. JAMA. 1995 Apr 19;273(15):1179-84. PMID: 7707624.

Erikssen G, Liestøl K, Bjørnholt J, Thaulow E, Sandvik L, Erikssen J. Changes in physical fitness and changes in mortality. Lancet. 1998 Sep 5;352(9130):759-62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)02268-5. PMID: 9737279.

Hagberg JM. Exercise, fitness and hypertension. In: Boughard C, Shephard RJ, Stephens T, et al, eds. Exercise, Fitness, and Health: A Consensus of Current Knowledge. Champaign, Ill: Human Kinetics; 1990:455–466.

Parkkari J, Natri A, Kannus P, Mänttäri A, Laukkanen R, Haapasalo H, Nenonen A, Pasanen M, Oja P, Vuori I. A controlled trial of the health benefits of regular walking on a golf course. Am J Med. 2000 Aug 1;109(2):102-8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00455-1. PMID: 10967150.

Thomas ZM, Wilk KE. The Golfer's Fore, Fore +, and Advanced Fore + Exercise Program: An Exercise Series and Injury Prevention Program for the Golfer. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2023 Jun 1;V18(3):789-799. doi: 10.26603/001c.74973. PMID: 37425113; PMCID: PMC10324324.

Gladdines S, von Gerhardt AL, Verhagen E, Beumer A, Eygendaal D; GRIPP 9 study collaborative. The effectiveness of a golf injury prevention program (GRIPP intervention) compared to the usual warm-up in Dutch golfers: protocol design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2022 Jul 26;14(1):144. doi: 10.1186/s13102-022-00511-4. PMID: 35883102; PMCID: PMC9327285.

Gosheger G, Liem D, Ludwig K, Greshake O, Winkelmann W. Injuries and overuse syndromes in golf. Am J Sports Med. 2003 May-Jun;31(3):438-43. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310031901. PMID: 12750140.

Baker ML, Epari DR, Lorenzetti S, Sayers M, Boutellier U, Taylor WR. Risk Factors for Knee Injury in Golf: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2017 Dec;47(12):2621-2639. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0780-5. PMID: 28884352; PMCID: PMC5684267.

Ehlert A, Wilson PB. A Systematic Review of Golf Warm-ups: Behaviors, Injury, and Performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2019 Dec;33(12):3444-3462. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003329. PMID: 31469762.

Fradkin AJ, Cameron PA, Gabbe BJ. Golf injuries–common and potentially avoidable. J Sci Med Sport. 2005;8(2):163–170. doi: 10.1016/S1440-2440(05)80007-6.

Coughlan D, Taylor MJ, Jackson J. THE IMPACT OF WARM-UP ON YOUTH GOLFER CLUBHEAD SPEED AND SELF-REPORTED SHOT QUALITY. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2018 Aug;13(5):828-834. PMID: 30276015; PMCID: PMC6159497.

McHugh MP, O'Mahoney CA, Orishimo KF, Kremenic IJ, Nicholas SJ. Importance of Transverse Plane Flexibility for Proficiency in Golf. J Strength Cond Res. 2022 Feb 1;36(2):e49-e54. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000004167. PMID: 35080209.

Tsai, Yung-Shen & Sell, Timothy & Myers, Joseph & Laudner, Kevin & Pasquale, Maria & Lephart, Scott. (2004). The Relationship between Hip Muscle Strength and Golf Performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 36. S9. 10.1249/00005768-200405001-00042.

Wells GD, Elmi M, Thomas S. Physiological correlates of golf performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2009 May;23(3):741-50. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181a07970. PMID: 19387406.

Uthoff A, Sommerfield LM, Pichardo AW. Effects of Resistance Training Methods on Golf Clubhead Speed and Hitting Distance: A Systematic Review. J Strength Cond Res. 2021 Sep 1;35(9):2651-2660. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000004085. PMID: 34224506.